Stones Corner Heritage Trail

Discover Stones Corner's heritage on a self-guided walking tour.

Rummage through retail history and discover the rags-to-riches story of how Stones Corner evolved from a crossroads way station to a renowned commercial destination.

Originally known as Burnett Swamp, this 19th Century bush thoroughfare to the city was soon a sought-after suburb for a growing class of entrepreneurs and financiers.

There are 11 points of interest along the 2.3 kilometre self-guided trail through the historic high street and nearby landmarks between Burnett Swamp Bridge and Langlands Park.

Stones Corner Heritage Trail map

The trail begins at Burnett Swamp Bridge on Logan Road near Old Cleveland Road and continues down Logan Road to Montague Street. It then heads up Ellis Street and Knowsley Street, crosses Old Cleveland Road, and finishes at Langlands Park in Panitya Street.

Download the trail guide for more images and information, or follow the map and stories online as you go.

For more information about each location, search Local Heritage Places online or the Queensland Heritage Register.

Introduction

Stones Corner takes its name from early European resident James Stone, who bought land between Logan and Cleveland Roads in 1875. He cleared the dense scrub to build a two‑room slab hut for himself and his wife, Mary Ann. He planned to sell alcoholic beverages to weary travellers along the busy roads but, when unable to get a liquor license, began brewing and selling ginger beer instead. His enterprise became notable enough that the area became known as Stone’s Corner (now Stones Corner).

New residents trickled into Stones Corner throughout the 1880s but were hampered by the long journey to and from the city. Mr Stone later reminisced to The Telegraph in 1924 that “in every direction stretched the bush, unknown and forbidding.”

In 1883, a horse-drawn omnibus service made Stones Corner more accessible to European arrivals, and the suburb continued to grow. Several large nearby estates, Knowsley, Langlands, Thompson, Logan Road, and Baynes, were subdivided and lots were sold to new residents. Local shops sprung up along Logan Road, which remains the ‘high street’ of Stones Corner today.

By 1887, Stone had sold his property for 25 times its purchase price. The following year his hut was replaced by the Junction Hotel, later known as Stones Corner Hotel. In 1890, it was leased to Thomas Delaney, who practiced Druidism. For the next few years, the hotel became the meeting place for a local Druid group that gathered for rites, initiations and ceremonies. It was just one of several lively community groups forming in the growing suburb.

In 1893, Stones Corner was severely impacted by a flood. The Telegraph reported how Norman Creek became “one vast sheet of water”, swelling to engulf Stones Corner and leaving only the tops of the hills above water. Locals were completely cut off from the city, having to use boats to secure supplies and to seek refuge until the waters receded. Another flood submerged the area in 1898.

Stones Corner recovered quickly from these disasters, and by 1902 an electric tram made the Logan Road shopping strip more accessible. The area grew in popularity and by the 1920s was a popular commercial hub with a bustling high street, active community groups and a lively sporting scene.

In its early days, Stones Corner was part of the sprawling Bulimba Division that stretched across much of south-east Brisbane. In 1888, the Shire of Coorparoo separated from Bulimba, with Stones Corner lying on the border between Coorparoo and the Division of Stephens. Stones Corner was integrated into the City of Greater Brisbane in 1925. It remained a suburb in its own right until 1975, when it was absorbed into the neighbouring suburb of Greenslopes. In 2017 after a successful 2-year campaign by residents Stones Corner regained its status as a separate suburb.

Points of interest

Logan Road, Stones Corner

Get directions

The Burnett Swamp Bridge, then known as the Buranda Bridge, shortly after its construction. Stones Corner, 1929. (Brisbane City Archives)

Through the 1850s, Burnett Swamp was subdivided and sold off as lush pastoral land. By 1865, a simple causeway and culvert crossed the creek to reduce flood danger, but locals soon saw it as inadequate.

By the late 1880s there was much local interest and discussion about how a new bridge would be designed and funded. The proposed bridge sat on the boundary between the Coorparoo Shire Council and the South Brisbane Municipal Council, and The Telegraph in 1893 reported:

…it is a standing subject for discussion in all the divisions interested in the building of a new bridge. Lacking everything else to talk about, councils easily fall back upon the Burnett Swamp Bridge. The spot is historic. … That old bridge is the Waterloo of the south side.

It took at least 5 years of planning and negotiation between a variety of governing bodies before the new bridge construction was completed in 1894. The Telegraph described it as a “handsome wooden erection, standing on 38 piles driven 32 feet into the bed of the swamp … with a footway on each side, and 4-inch hardwood decking.”

Despite this great effort, the new wooden bridge was soon outmoded. Having been built for horse-drawn carriages, it quickly fell into disrepair as motor cars came into use during the 1910s. By 1925 the bridge was in a dangerous condition and a new one designed under the supervision of C.B. Mott, the first design engineer of the newly formed council of Greater Brisbane, was completed in 1928. Named the Buranda Bridge – though it continued to be popularly called the Burnett Swamp Bridge like its predecessors – the new bridge proved far more durable. After almost a century, despite many destructive floods, it remains in use today.

For more information about this local heritage place, refer to the Brisbane City Council Local Heritage Places website.

273 Logan Road, Stones Corner

Get directions

Thomason's Buildings, Brisbane, 1952. (State Library of Queensland)

One of the first tenants was Olga Evans in 1926, a dressmaker who operated from an upper floor. A Queensland National Bank branch operated from a lower floor, making it the third bank to operate in the small suburb. No longer just a crossroads way station, Stones Corner was becoming a local retail and commercial hub, attracting a burgeoning class of entrepreneurs and financiers.

With commercial success came a growing sense of a local identity. Having their own banks, shops and services meant residents no longer travelled to Woolloongabba or Bulimba, and their money stayed in Stones Corner.

Local business owners were keen for progress. In 1926, The Telegraph reported a Mr H Shaw, who claimed that “Woolloongabba was cribbing Stones Corner’s trade” and that Stones Corner “wanted to be self-centred.” In 1928, the Stones Corner Business Men’s Association was formed and lobbied for an official post office in the growing centre. They wanted it to replace the post office agency that operated from the local pharmacy.

Thomason’s Buildings remained a key landmark and commercial premises throughout this time. The bank stayed on the lower floor, changing its name in 1948 after successive takeovers that ended with the National Australia Bank. The rear of the building hosted a fruit and produce merchant during the 1950s.

For more information about this local heritage place, refer to the Brisbane City Council Local Heritage Places website.

Note: This is a private property.

303 Logan Road, Stones Corner

Get directions

Pharmacy, Stones Corner, c. 1928. (State Library of Queensland)

Advertisements in The Brisbane Courier during the late 1890s showcased a wide range of products sold by Thomason Brothers. Thomason’s Hair Restorer that “not only restores the hair to its original colour, but promotes the growth and removes dandruff”, and Thomason’s Corn Cure as a “Sure and Speedy Cure for a Pet Corn”.

Other available products were of a more hazardous nature. Highly corrosive picric acid, used in producing explosives during the First World War, was advertised by Thomason’s as a household chemical. It was promoted as something that should be kept in every home for treating burns and scalds, a common prescription then. The poison Thomason’s Phosphorous Paste was touted to deal with rats, mice and cockroaches, to be “spread on bread and placed near their haunts”. In 1897, a magisterial inquiry found that a vial of strychnine, a potent poison sold by Thomason’s, had been a local man’s cause of death.

In 1919, Thomason’s pharmacy was sold to William Pearce, another pharmacist, before passing between various pharmacists. In 1923, half of the shop remained a pharmacy while the other half was taken over by the Commonwealth Bank and the Stones Corner Post Office. At a time when mail and telegraph were the only long‑distance communication methods, the store became an invaluable community hub. It connected Stones Corner with the rest of the world.

However, the small post office agency was also a source of concern for the local business community. In 1926, a delegation presented the Postmaster-General with a petition from more than 500 residents asking for a larger post office at Stones Corner. R.M. King, a local politician with the delegation, said he had seen the locality grow from nothing to its current state. He felt that Stones Corner would soon rival Fortitude Valley as a major centre of Brisbane.

In 1928, the request was granted, and a better-equipped post office was established in Stones Corner. This was a key milestone, as post offices were required to bring in £400 annually (approximately $38,000 today), which required a high volume of customers. The Thomason Brothers & Co. Buildings continued to host a variety of shops and services, including the post office, into the 21st Century.

For more information about this local heritage place, refer to the Brisbane City Council Local Heritage Places website.

Note: This is a private property.

286 Logan Road, Stones Corner

Get directions

A similar design to those in Stones Corner, air raid shelters at North Quay were built to be converted to bus passenger shelters after the war. Brisbane, 1949. (State Library of Queensland)

Before public shelters were built, residents would shelter at home during regular blackout drills. One drill in August 1941 required everyone in South Brisbane to turn off lights and cover windows so no light was visible.

The Telegraph reported one resident’s nonchalant attitude during the air raid drill:

It was arranged that the whole family should spend the period of darkness in my bedroom, so, quite early in the day, I climbed up on a chair, preparatory to draping a rug across the window. […] I then inspected my reading lamp to make sure it was in good working order, laid out a little light literature, cut a few egg and lettuce sandwiches in case of emergency, and felt reasonably satisfied that we were prepared for the worst.

In 1941, the bombing of civilian areas, such as the Blitz in England and Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, led Australia to increase air raid precautions. The Imperial Japanese Navy bombing of Darwin in February 1942 made the threat of air raids a stark possibility. Brisbane was Australia’s northernmost major population centre and considered exposed to possible air and sea bombing attacks. With Brisbane becoming the Allied Forces headquarters in the South West Pacific during 1942, it was seen as a potential target and the government furthered efforts to protect civilians.

As part of its civil defence measures, Brisbane City Council constructed air raid shelters throughout the city, including Stones Corner. Its surface air raid shelters were designed by the City Architect, Frank Gibson Costello. They included the standard pillbox type of reinforced brick or concrete with solid walls and a solid roof. Other examples were a bus shelter with a single cantilever roof and a park shelter with a double cantilever roof.

The Stones Corner Air Raid Shelter was a park shelter type, originally enclosed by masonry walls to create a sturdy rectangular pillbox. It was designed so the walls could be removed after the war, transforming the structure into the bus shelter it is today. Despite the ongoing war, Brisbane remained optimistic and attentive to the small details of urban development.

For more information about this Queensland Heritage Place, refer to the Queensland Heritage Register.

310 Logan Road, Stones Corner

Get directions

A front elevation architectural sketch of the Commonwealth Bank of Australia at Stones Corner. Construction documents, 1937-40. (National Archives of Australia)

Traditionally, banks were designed to evoke a sense of security, solidity and permanency, drawing on Neoclassical, Beaux-Arts and Gothic architectural styles. Imposing columns, sturdy masonry and well-ordered symmetry conveyed to potential customers that banks could be trusted to safely and responsibly keep their finances. A local exemplar of this style can be seen in the Bank of New South Wales at 33 Queen Street, Brisbane City.

The Stripped Classical style of the Commonwealth Bank at Stones Corner maintained these same values while drawing stylistic influences from the Art Deco movement. Originating in France and becoming popular elsewhere after the First World War, Art Deco design drew inspiration from emerging technologies. It adopted the sleek, aerodynamic forms of motor cars, aircraft and ships and applied the same principles to buildings. The Art Deco influence appears in the rounded edges, smooth surfaces and parallel speed lines on the bank’s parapet. These features gave the building a strikingly modern look for the time.

For more information about this local heritage place, refer to the Brisbane City Council Local Heritage Places website.

Note: This is a private property.

357 Logan Road, Stones Corner

Get directions

Penney's building, The Courier Mail, Brisbane, 1938. (National Library of Australia)

By the 1930s, Stones Corner had grown enough to attract the attention of a giant in the retail world. Shipping magnate James Burns had founded Penneys earlier in that decade and it quickly grew to almost 40 department stores throughout Queensland and New South Wales.

This store, the first suburban Penneys branch, opened on 8 September 1938 to crowds of eager shoppers. Both in form and function, this was a step beyond the vibrant array of smaller shops that had grown throughout Stones Corner in the 1920s. Its striking Art Deco façade, skylit interior, and glass and chrome counters proclaimed the coming of a new age of modern consumerism. Unlike the small family businesses and local shops nearby, Penneys had a complex and hierarchical structure with intensely trained staff governed by executive ranks instituting corporate policies. It was a corporation in the modern sense.

The arrival of such a store indicates how much Stones Corner had grown by the late 1930s. In 1938, the Truth newspaper described the suburb as a “big industrial and business area”, and reported on the store opening:

"…their displays will be made in open glass containers, behind which courteous assistants will attend to the needs of the 24,000 people who, it is estimated, live in the area which forms the hinterland of Stones Corner. Officials of Penneys have calculated that there are 6000 homes, with an average of 4 persons to each home, in the district, and decided that the establishment of a store was justified."

With the arrival of a store comparable to those in Queen Street or Fortitude Valley, Stones Corner became a shopping hub. It attracted residents from Buranda, Coorparoo, Greenslopes and Holland Park.

For more information about this local heritage place, refer to the Brisbane City Council Local Heritage Places website.

Note: This is a private property.

Logan Road, Stones Corner

Get directions

The Alhambra Theatre entrance advertising the screening of 1947 American film, 'Road to Rio', starring Bing Crosby and Bob Hope. Stones Corner, 1949. (State Library of Queensland)

A decade later, the strip provided more than simple necessities, offering a variety of bakeries and fresh produce vendors, Mrs Seils for wine purchases, and Thomason’s for pharmaceuticals. A tailor, plumber, hairdresser and blacksmiths provided the conveniences of suburban life.

By the 1920s, it had become a hub for shoppers throughout south Brisbane. It grew to include a dentist, pastry chef, costumer, electrician, illuminator, jeweller, bicycle repairman, banker, draper, milliner, dressmaker and a mechanic. A store run by Mrs Laura Bates was simply listed in the 1921 post office directory as selling ‘fancy goods’.

The 1930s saw the arrival of even more modern establishments, from the large Penneys department store to a vegetarian café. Some buildings from this era can still be seen throughout Stones Corner today. Uhlmann’s at 365 Logan Road was named after Royston Douglas Uhlmann, a local butcher who had operated in the area. Similarly, the Galloway’s building at 329 Logan Road owes its name to Ronald Fraser Galloway who established several grocery stores throughout the area. Also originally a grocery store, Galloway’s was leased by the neighbouring Woolworths in the 1960s.

Nearby buildings show Art Deco influences on Stones Corner. Not unlike Penneys and the Commonwealth Bank, the striking façade of 337 Logan Road is an illustration of this architectural movement. From the 1930s it was a drapery under George Henry Stewart, who grew from humble business beginnings to be a respected local purveyor of fine menswear. By the mid-1930s, Stewart’s was the kind of chic, fashionable establishment that would characterise the emerging Stones Corner high street.

Perhaps the most significant building of this period was the Alhambra Theatre that once stood at 38 Old Cleveland Road, opposite the hotel. Renovated after fire damage around 1929, its ‘tropical theatre’ design with lofty windows providing ventilation to withstand the summer heat was typical of Queensland at the time. It was through the Alhambra Theatre that Stones Corner was introduced to the blockbuster American films captivating audiences across the country.

The Alhambra Theatre survived into the 1960s, by which time the earlier local shops of Logan Road were dwarfed by newer developments. More industrial enterprises, such as the Drouyn drum factory at 382 Logan Road, were established on the edges of the main strip. The Drouyn drum factory was Australia’s only local concert‑band instrument maker and also supplied instruments under contract to the Australian military. Drouyn’s products could be heard on the radio and seen on television screens throughout the 1960s and 1970s, but the factory closed in the late 1980s.

The Logan Road shopping strip has remained a busy hub into the 21st Century. In the early 2000s, Stones Corner became a retail destination for discounted clothing factory outlets. An array of cafes, vintage clothing and boutique shops remain in the high street today, providing a lively village atmosphere.

3 Ellis Street, Stones Corner

Get directions

A picture of Salvation Army Hall as it appeared in 'The Telegraph', 1926. (National Library of Australia)

If a member became seriously ill or passed away, the society would make payments to them or their dependents. In early Brisbane, funeral costs or lost income from illness could place families under severe financial strain. This kind of medical and life insurance was therefore an invaluable asset.

After the opening ceremony, the local Oddfellows of the Loyal Native Rose Lodge initiated several new members. This brought total membership to 83 people from Stones Corner and Coorparoo. In the years that followed, the hall continued to be the meeting place for the growing Lodge. The Brisbane Courier on 29 January 1891 described a typical gathering:

"A very enjoyable social meeting was held on Tuesday under the auspices of the Native Rose Lodge Oddfellows’ Social Club at their hall, Knowsley Estate, Coorparoo, about 250 ladies and gentlemen being present. […] A sailor’s hornpipe from Mr. Daniells and an Irish jig from Mr. Mulcahy were much appreciated. The string band from the Loyal Kangaroo Lodge was present. Music, dancing, card-playing, and draughts were indulged in until about midnight."

However, in a fashion typical of friendly society halls, it was also used as a wider community space to host religious sermons, political organisations and youth groups.

By the 1910s, another friendly society – the Ancient Order of Foresters – was regularly gathering in the hall. Like the Oddfellows, the Order of Foresters had branches known as ‘Courts’ throughout Australia. They were known as ‘Courts’ and drew inspiration from British myth and folklore, such as the tale of Robin Hood, in the design of their regalia and symbolism. The Stones Corner branch was known as ‘Court Progress’ and included around 50 members. Due to their presence, 3 Ellis Street became known as Foresters’ Hall from the 1910s onward. It continued to host a variety of religious and secular events for other community groups, such as the local Red Cross Society.

In 1925, the hall was bought by the Salvation Army. They relocated a smaller hall from Edith Street and placed it behind the main hall. At the time, the main hall was widely known as Knowsley Hall, named after the Knowsley Estate on which it was built. Having a permanent location within the area was a boon for the local Salvation Army. A hall meant permanence, as declared by their Commissioner at the official opening of the building. Indeed, the Salvation Army Hall – as it became known – would remain a key hub for the Salvation Army and the broader community until 1998.

In more recent times, the larger hall was adapted into private residences and the smaller into commercial premises.

For more information about this local heritage place, refer to the Brisbane City Council Local Heritage Places website.

Note: This is a private property.

19 Knowsley Street, Stones Corner

Get directions

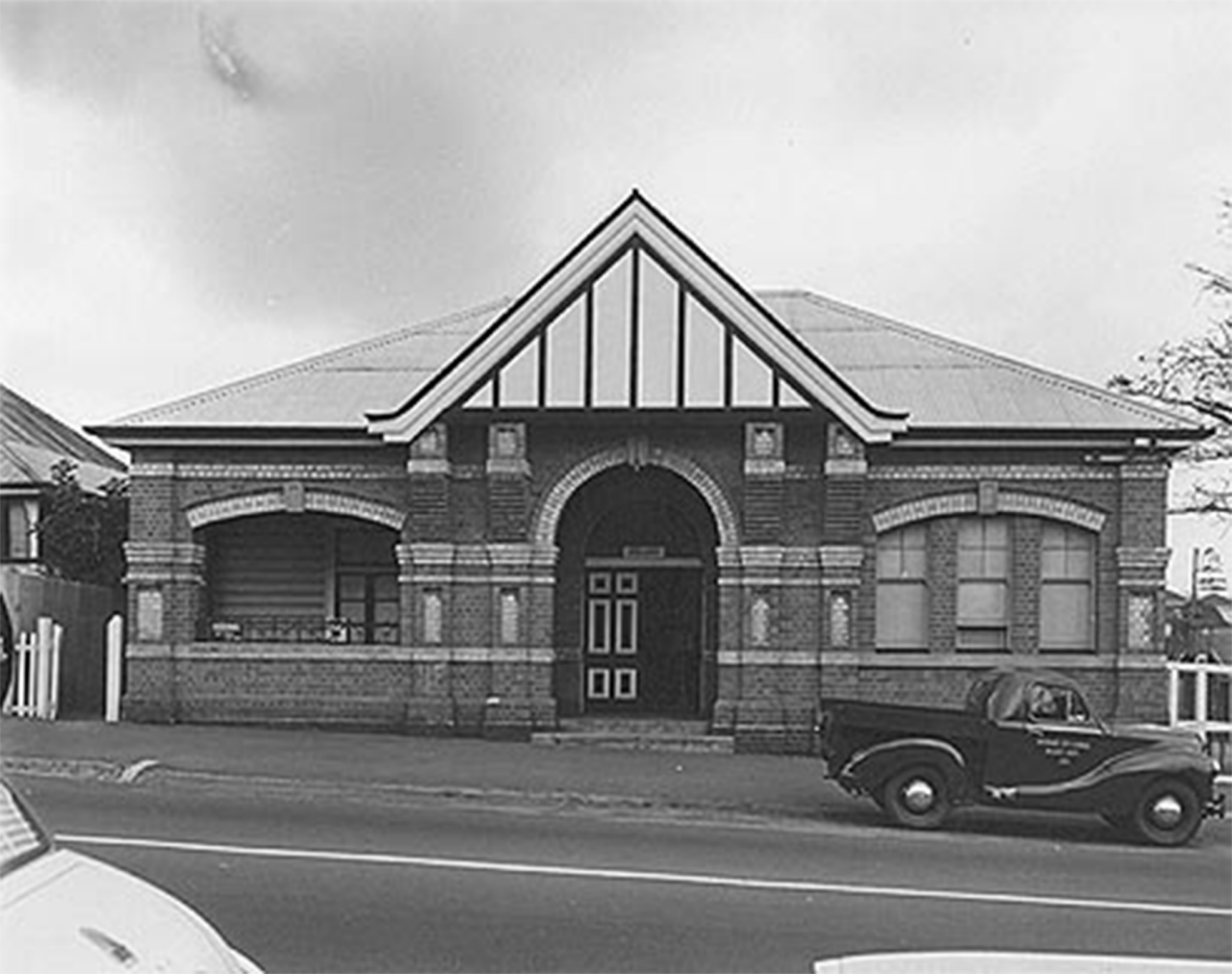

Coorparoo Police Station, Coorparoo, c. 1940 (Queensland Police Museum).

Alongside the rapid growth of Stones Corner, the 1920s saw a rise in petty crimes by youth gangs. Their vandalism and harassment became a cause for concern among locals. At times, this petty crime gave way to more serious incidents. In 1925, a young man armed with a revolver attempted to hold up the store of Bernard and Prudence Stone. The Telegraph reported that Prudence had arrived at the store to find her husband held at gunpoint. “Hello, what’s this! You’re young to be doing this kind of thing!” She snapped, before tossing the cash box to the robber, saying, "Take it, you scamp!” When questioned in court why she was not more nervous, Prudence simply explained, “I have been two years under air raids, and am very, very used to that sort of thing.” She requested the court show leniency to the robber, who had since been apprehended.

In 1925, The Brisbane Courier reported that ratepayers had petitioned the council to curtail the “increasing larrikinism of Stones Corner”. In 1928 it reported that, despite an extra police officer assigned to the area, things were going from bad to worse. Further petitions called for a stronger police presence to halt the destruction of property and disorderly conduct by people of the larrikin type.

As a result, the Coorparoo Police Station was relocated to Stones Corner in 1929 to be closer to the emerging business centre. Its building followed a residential design typical of suburban police stations at the time. It included space for a police officer to live, which allowed it to be staffed full time.

During the Second World War, the station doubled as a base for the Air Raid Precautions (A.R.P.), whose wardens were charged with running blackout drills, handing out gas masks, guiding civilians to air raid shelters, and all other measures required to protect people in the case of air raids. The resident police officers doubled as A.R.P. wardens, and a small A.R.P office and air raid shelter were erected beside the police station.

For more information about this local heritage place, refer to the Brisbane City Council Local Heritage Places website.

12 Main Avenue, Stones Corner

Get directions

Coorparoo Substation No. 210, c. 2020 (Queensland Government).

However, this new technology did bring challenges. Throughout the 1920s, a series of fires caused by faulty wiring and electrical failures destroyed Stones Corner houses and shops, and people were injured by contact with live wires. Electricity was still a new technology and safety standards had not yet developed to account for its hazards.

Nevertheless, by the late 1920s the demand for electricity had increased so much that new infrastructure was needed. Powerhouses were built at New Farm and Bulimba to supply electricity across the city. A network of substations then stepped down the high‑voltage output for suburban areas and dispersed the heat generated in the process.

The Coorparoo Substation No. 210 had no regular staff, nor would consumers have had any reason to visit. Yet its designer, Reyburn Jameson, still paid close attention to its appearance. He ensured it would be an attractive addition to the residential streetscape where it was built. Its façade is influenced by the Spanish Mission style, which had become popular in 1920s Brisbane as Australians were increasingly influenced by Californian architecture.

The fact that it was designed to be both functional and beautiful testifies to the importance of electricity during this period. The substation was not seen as merely a necessary piece of technical infrastructure, but a building worthy of pride and celebration – a marker of progress and development. Though it was decommissioned by 1977, the substation remains a reminder of a pivotal development in Brisbane history.

For more information about this Queensland Heritage Place, refer to the Queensland Heritage Register.

Note: This is a private property.

31 Panitya Street, Stones Corner

Get directions

Politician Fred Bromley makes the first kick for the Junior Rugby League season at Easts League Club, Langlands Park, 1948 (State Library of Queensland).

By the early 1900s, organised football and rugby games were being played at Stones Corner. The suburb was developing its own teams and an official sportsground was needed. So, in 1912 the Coorparoo Shire Council resolved to purchase a large area of Langland Estate for use as a field, park and recreation reserve. It purchased the park in 1915, naming it Langlands Park after the estate, and it quickly became a key leisure hub for Stones Corner.

After the First World War, Langlands Park gained several improvements, including the grand memorial gates now at the Langlands Park Memorial Public Pool. Throughout the 1920s, concerts were held at the park grandstand and the lush open area provided an ideal venue for fetes and festivals, such as the Coorparoo Show. A lively sporting scene developed and one field was maintained by the Eastern Suburbs Cricket Club, later known as the Easts-Redlands District Cricket Club. In 1937 a 150-seat grandstand was built for their cricket matches, owing to their popularity.

Another field was used by the Coorparoo Rugby League Club, known today as the Brisbane Tigers. The club first appeared in 1917 with the name Coorparoo but by 1933 was playing as the Eastern Suburbs Tigers. It was coached by Tom Bird, a retired local sports legend who had become a mainstay as manager of the Stones Corner Hotel. Almost a century later, Langlands Park remains the club’s home stadium. Bare fields on which the players once practised are now the Easts Leagues Club complex that covers much of the park and seats thousands of visitors on game days.

For more information about this local heritage place, refer to the Brisbane City Council Local Heritage Places website.

Note: This is a private property.

Do you have any feedback?

We'd love your feedback on this heritage trail experience and ideas for future local heritage trails.

More trails to explore

Brisbane City Council's heritage trails celebrate the city's history, including local heritage places.